Over the past month or so I have been in that strange liminal world of unwellness, where you are drifting on the edges, looking in at the things you can’t do and grieving because you can’t do them. I’ve missed so much big and important stuff at work, and have felt the inevitable guilt and sense of failure that comes from a life-time of social conditioning around illness being a personal failure. I have been watching, with dismay, the Westminster Theatre of Cruelty unfold as I’ve been unwell.

The current government’s proposed ‘reforms’ to the welfare bill, framed as measures for positive change and encouraging engagement with work, face a righteous and formidable tide of opposition. While some concessions on the bill have been offered, these have been largely ill-received, creating a perceived two-tier system of benefits that remains inherently harsh and will undeniably harm vulnerable individuals. These concessions, it is crucial to note, do not stem from a moral shift within the government, but rather from a pragmatic desire to stave off a backbench rebellion and maintain a firm stranglehold on power. Critiques from across the political and charitable sectors, alongside widespread public concern, consistently highlight the potential for these changes to push vulnerable individuals into extreme poverty. Within the specific mechanisms of this legislation, elements emerge that strike not just as impractical, but as profoundly cruel. Consider, for instance, the proposed tightening of Personal Independence Payment (PIP) eligibility: under the revised points system, an individual unable to perform a fundamental act of self-care, such as washing themselves below the waist, might not qualify for essential support if they present with no other complex needs. In a nation purportedly upholding dignity, such an outcome is not merely unjust; it is obscene.

This legislative agenda, however, is merely a symptom of a far deeper systemic malaise. It represents a pervasive, broken approach to health and well-being that dehumanises the individual. Illness and disability are too often misconstrued not as acute challenges demanding support, but as character flaws – personal deficiencies in drive or moral fibre. This perspective wilfully ignores the escalating crisis of poor health across the UK, a crisis inextricably linked to systemic poverty and a prevalent culture of work that is frequently devoid of meaning, often physically damaging, and inherently demeaning. The Cabinet, in particular, is increasingly appearing as an arrogant and detached cabal of individuals with no practical understanding of the lived experience of those navigating illness and disability. It is becoming increasingly apparent that a better societal model is not only possible, but desperately needed. What is required is a fundamental paradigm shift in how we perceive ill health, disability, and the varied capacities for work; these are not inherent defects in the individual, but rather real-world systemic problems, demonstrably exacerbated by the environment in which we live and work. My own life serves as a stark illustration of this critical failure.

From the age of thirteen, having been raised in a working-class family where contribution was encouraged, I embraced work. My parents wanted us to learn the value of money and to take responsibility for ourselves. We didn’t have to contribute to the running of the family home, but it was clear that money was finite and if you wanted something, you either had it as a gift for birthdays or Christmas or you bought it yourself. Whether it was in my great uncle’s newsagent shop, as a babysitter or nanny, or in physically demanding summer jobs through university, the principle that “there’s no such thing as a free lunch” was deeply ingrained. The single summer spent claiming unemployment benefits during my university years was among the most miserable and isolating periods of my early adulthood, reinforcing my intrinsic desire to contribute.

The challenges I found myself having to face were not for want of effort. Issues I had navigated since childhood – emotional overwhelm, profound fatigue, and a deep-seated need for periods of solitary recovery from overstimulation – found no accommodation within the conventional workplace. While my mother had intuitively allowed me necessary respite as a child, the professional world offered no such understanding. I internalised the crushing belief that something was horribly wrong with me, that I was useless, lazy, and incompetent for simply not being able to perpetually cope, work, and be well. In response, I pushed myself relentlessly, always striving to go above and beyond, volunteering for every opportunity – even as my body and mind silently rebelled, resulting in frequent absences from unsustainable environments and situations. This was not a character flaw; it was the direct consequence of navigating undiagnosed ADHD and chronic fatigue, and an unspoken expectation of ‘presenteeism’ that offered no quarter for my particular human frailty.

The inherent pressures of the workplace became devastatingly clear in 2006. Just weeks after returning from a significant mental health breakdown, I fell from a horse on Cleethorpes beach. While the immediate emotional trauma of the incident is a distinct and complex narrative, the physical consequences proved to be life-altering. The crucial detail, and indeed a stark indictment of systemic oversight, was the missed diagnosis of an L1 vertebral fracture by the Accident & Emergency department. Dismissed with advice for soft tissue damage, I was sent home, unknowingly carrying a broken back. Had this severe injury been correctly identified, the protocol would have been a long period of sick leave, recognising the danger of physical exertion. Yet, burdened by the recent three-month absence due to my breakdown, and met with a dismissive response from my superior when I reported the fall, I made a reckless decision. After only one week of ‘convalescence,’ I returned to work, enduring constant, screaming agony. This decision, driven by fear of professional judgment, set in motion a profound and irreversible deterioration of my health.

Within a year, I developed Chronic Migraine Syndrome; within two, the debilitating onset of Ulcerative Colitis. My absenteeism from work escalated dramatically, not from choice, but from an inability to function amidst relentless pain, severe mental health instability, and the terrifying, unpredictable nature of my new conditions. The fear of public accidents due to ulcerative colitis, for instance, led to months of social isolation. Concurrently, the physical environment of the college where I worked became actively detrimental: harsh lighting, oppressive heat, and incessant noise fostered overwhelming sensory overstimulation, leaving me profoundly depleted, miserable, and suffering from debilitating headaches by day’s end. By 2012, acknowledging the unsustainability of my situation, I made the decision to leave stable employment with no immediate prospects. This step, born of sheer exhaustion and inability to cope, was a direct consequence of a healthcare system’s initial failure to diagnose my injury and a workplace culture that fostered an environment of fear over welfare.

The hope that self-employment might offer a panacea proved to be an illusion. Driven by the direct link between work and income, I found myself pushing even harder, often working in situations where I demonstrably should have been resting, only exacerbating my illnesses. This relentless cycle continued until a comprehensive diagnosis in 2017 revealed PTSD-induced fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, and pervasive chronic pain – a recognition of the ‘wreck’ my body had become. While I accept responsibility for the initial accident – I was not a good enough rider to be on a horse of her size and power and should have had better judgment – its cascading consequences, amplified by systemic failures and an unforgiving societal framework, irrevocably altered the trajectory of my life. My daily reality remains one of persistent pain, fluctuating mobility, profound fatigue, and ongoing, undiagnosed ADHD, forcing difficult decisions about future economic activity. This reality is not a choice; it is a life being lived, and the prospect of being further penalised for this trajectory by welfare policies is, quite frankly, despicable.

I am far from alone in having forced myself into work when seriously unwell, overriding the sensible human impulse to rest. This compulsion stems from a deep-seated fear: fear of negative judgment, fear of losing a job, or fear of punitive HR procedures. We do not inhabit a culture that genuinely makes space for rest, recovery, or convalescence. Instead, these fundamental human needs are perceived to diminish our value as a viable economic unit of productivity. In the relentless pursuit of growth under late capitalism, driven by the ruling elite’s obsessive work agenda, the message is clear: if you need bed rest, if you need time out, if you are unwell—mentally, physically, psychologically, or emotionally—then you are inherently at fault. Period.

This brutal, Victorian work-time discipline, utterly counter to human well-being, must be robustly questioned, challenged, and ultimately undermined. The pervasive fear of harsh judgment for illness or disability makes life extraordinarily difficult. My own experience with mobility issues underscores this: using a walker in public, I frequently felt like a nuisance, perpetually in everybody’s way due to my slower pace or the space I occupied. The audible “tut” of impatience from passers-by reinforced this perception, embarrassing me to present publicly as a person in need of a mobility aid. This ingrained societal judgment, born of a system that prioritises relentless output over human fragility, is not just pervasive, but deeply damaging.

Beyond Economic Units: Reclaiming Our Human Value

The relentless drive of our workplace culture often attempts to force individuals into neat boxes of productivity, stripping away the very essence of our humanity. Yet, each human being is an individual with unique needs, flaws, and strengths. We are complex, interesting, and holistic beings; we simply do not fit into tidy, pre-defined categories. I want a future where the stigma, blame, and punitive policies ingrained in current HR practices vanish entirely. In this future, we are all recognised as finite beings, not endlessly exploitable machines. Everyone requires rest, everyone needs care, and everyone will, at some point, experience illness or pain. This is an intrinsic part of the human experience, not something separate or a personal failing. It is simply how humans are built; we are not, by design, machines.

One of the hardest consequences of illness, all too often, is isolation. During my initial, acute struggles with ulcerative colitis I felt utterly detached from the world. The fear of having an accident in a public place left me housebound for months, consumed by the shame and stigma of such a possibility. I even woke up panic-stricken from dreams of these very accidents. This level of fear impacted my mental health, eroding my ability to cope with daily life, let alone the demands of a workplace. In that period of acute illness I became terrified of food and even of my own body. It took immense time and effort to move into recovery and remission – a state I’m fortunate to have maintained for a long time now, primarily through diet, despite a GP’s dismissive assertion that diet had “nothing to do” with my ulcerative colitis.

This systemic disregard for lived experience in policymaking is, in my view, deliberate. To this government, the disabled and unwell community are evidently a massive inconvenience. By deliberately depriving this community of resources and power, effectively rendering them completely dependent on draconian and vicious welfare measures, the aim appears to be to disempower and silence them. The implicit expectation is that people, desperate just to survive, will lack the energy to fight back.

Designing for Well-being: A Collective Responsibility

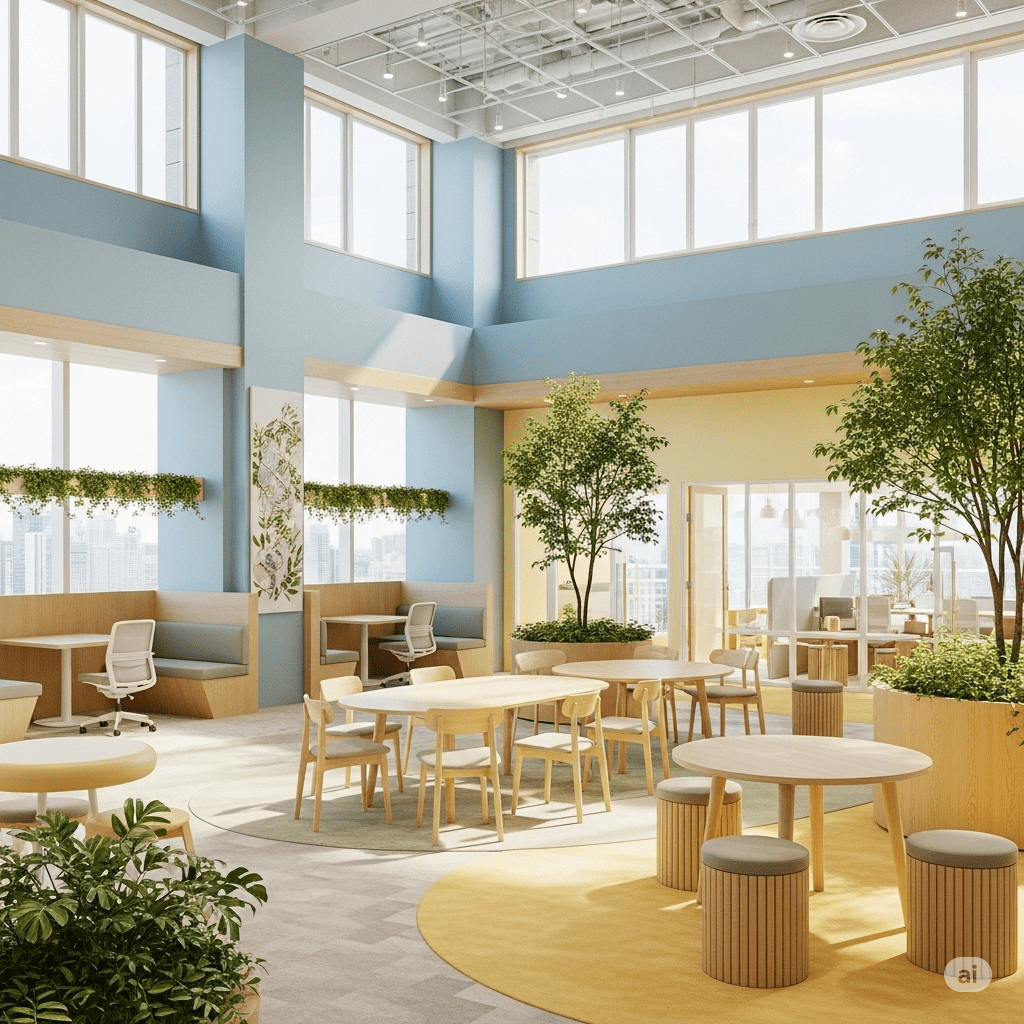

If our ambition is genuinely to improve the quality of life for everyone – in our workplaces, in our communities, and particularly for those of us living with disability and chronic poor health – we must critically examine our built environment. A significant proportion of our buildings, designed without genuine consideration for human well-being, are, quite frankly, violent in their exclusion. They are frequently noisy, overheated, difficult to navigate with narrow passages, and feature staircases that are hard or even impossible for many. The choice of lighting, and the presence or absence of natural light and fresh air, makes a big difference, not just to those of us who are unwell, but to everyone.

It defies logic that we collectively tolerate living and working in what are, in essence, ‘sick buildings’. For individuals like myself, who are hypersensitive to these environmental factors, the impact is immediate and overwhelming. The wrong lighting can induce unwellness within minutes. Excessive noise renders me incapable of focus, making it impossible to listen or process information. A lack of natural light triggers an immediate sense of deterioration. This is not an individual failing; it is a fundamental flaw in design.

The onus, therefore, lies not on the individual to ‘cope’ with hostile environments, but on society to cultivate a workplace and a workplace culture that is inherently healthy, inclusive, adaptable, and flexible. Such a transformation would significantly enhance the chances for individuals currently excluded from the workforce to not only access work, but to thrive within it. To place an ill person in a sick building is to guarantee their swift departure, as their capacity to cope will inevitably be overwhelmed. None of this burden should rest solely on individuals. This represents a monumental cultural and societal responsibility, demanding collective effort to devise sensible, future-focused solutions for how we live and work. Our aim must be to enable all of us to contribute, but critically, without that contribution being laden with the arbitrary value judgments, HR-driven pressures, and inherent cruelties that can so easily accompany life when you are living with illness.

The Myth of Scarcity: A Political Choice, Not an Economic Reality

The notion that our nation’s budget must be managed the same as a household’s, subject to the same constraints and limitations, is a pervasive myth. This fallacy, peddled by those in power, serves to obfuscate the true reality of economic priorities and resource allocation. It is a deliberate lie. The capacity of a sovereign government to invest in its people and infrastructure bears no resemblance to the modest budget of a small family. The speed with which funds materialise when a political will exists starkly exposes this deception. We need only observe the recent NATO declaration, where member countries committed five percent of their GDP to arms – a decision I find personally abhorrent and shocking. This is not a question of an empty treasury; it is exclusively a question of priorities, a question of political choice.

We possess the collective capacity to foster a society where everyone is genuinely cared for. We could ensure a decent standard of living, robust safety nets, truly flexible working arrangements, inclusive environments, and a far more adaptable and engaging approach to the entire world of work. This is entirely achievable, if it were the political choice. However, our current government remains dementedly committed to the false economy of endless growth. It wilfully ignores what true sustainability looks like, disregards the power of cooperation, and places, front and centre, the interests of capital and capital investment above all else. This is a deliberate political choice.

The public, crucially, is not naive. People recognise this underlying agenda and are beginning to question it with increasing force. My ongoing work, including my capacity for thought and effort amidst the constant navigation of chronic illness, is focused on fostering a major paradigm shift in how we, as a society, live and care for one another. This involves fundamentally altering how we perceive and respond to illness and disability; challenging the damaging myths that frame a limited ability to work as a personal failing rather than a systemic barrier.

There is no discernible appetite for war within the United Kingdom, in spite of the ceaseless propaganda and focus on war readiness. What is palpably evident, however, is a widespread weariness and a creeping degradation of people’s lives. This is a volatile combination that, if left unchecked or, worse, deliberately harnessed, could quickly become toxic and dangerous, particularly if exploited by the far right. True national security lies not in military excess, but in the collective well-being of its citizens – a robust social safety net, equitable access to support, and a societal infrastructure designed for human flourishing, not merely economic extraction. This paradigm shift towards a truly humane and inclusive society is not merely an aspiration; it is an urgent imperative.